Elephant Song – Sesfontein – Elephant Song

The previous days had all been a reliving of the memories we obsessed on during the Covid years. We had dreamed of getting back to Palmweg Concession, of camping at Xai As and Black Ridge, of driving to Hoanib. We both agreed that we felt purged. We had no desire to go back through the Palmweg concession, and in fact we had been ever so slightly bored by some of the driving. We even began to talk about what other trips we could do next year. This feeling didn’t last!

It was some time since we had been able to get to a shop, and we had run out of fresh vegetables several days ago. We’re vegans and usually rely heavily on vegetables, so today’s plan was to go to the (relatively) large village of Sesfontein. I guess in Namibian terms it was a town, it had a small hospital and more than one shop, plus a primary and secondary schools. It served as the main hub for the local area. As Nigel said, we were going to visit the ‘bright light’ of Sesfontein.

Nigel was born and brought up in Zimbabwe, so he is aware of some of the difficulties faced by people working and living in remote areas. We asked Magnus if there was anything he wanted from Sesfontein, and he asked us to take some food to his son, who had recently been kicked out of the school’s hostel. He was staying with a friend.

In these rural areas children don’t get the luxury of living at home for their secondary education. They travel to larger ‘towns’, and they are accommodated in hostels. We didn’t enquire why Magnus’ son had been kicked out, but Magnus was most anxious that his son continued his education uninterrupted.

We asked Magnus if he wanted anything for himself, and we got a shopping list which mainly consisted of meat and coca cola.

As we left, Nigel spoke to the French people who had been mock charged by Stompie yesterday. He told them that it wasn’t clever to get that close and disturb the elephants, especially if this caused them to get aggressive towards cars. They would become a nuisance to the area and be shot. The Frenchman excused their behaviour by saying he had been with Magnus (although they didn’t mention him by his name). However, Magnus said he told them to turn the engine off but they wouldn’t – presumably so they could keep the air conditioning on. It turned out that Nigel’s reprimand was the ultimate hypocrisy as we also got charged by Stompie when we were on foot (see Day 21)

We were just about to pack up to go to Sesfontein when Magnus pointed out the elephant family was returning. They were in the river bed immediately below the ridge where the campsite is. Slowly they meandered down the river bed and towards the west end of the Hoanib.

We were above them on the ridge. It was such a beautiful sight. There were four adults and three babies, one of which was very small.

Magnus said the baby was born in May, but we understood from someone doing a survey on the elephants, that the small baby was only four or five weeks old. The largest elephant was the matriarch, and Magnus said she was 55 years old. The elephant survey people said she was more likely 40.

By the time we met the elephant survey people a week or so later, we had already begun to realise that not all the ‘information’ we were given was accurate.

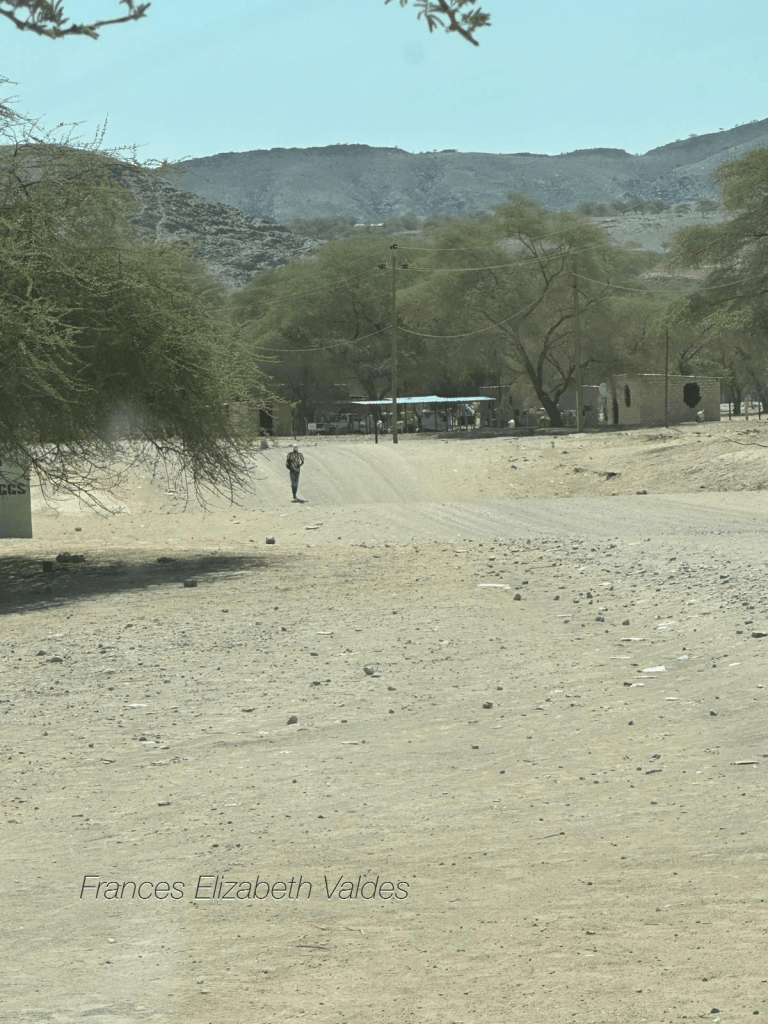

We drove through the sandy Okambonde Plains for an hour or so, and came to the ‘main’ dirt road leading from Sesfontein to Purros (more of which later). We knew Sesfontein reasonably well, not only from our 2020 visit, but also from when we had stayed in a beautiful lodge a little way from it in 2019. The town seemed smaller and less lively than before. There were signs of increased poverty everywhere. The people were so thin, and we thought there were both less shacks and less people.

The first place we went was to the Purros Conservancy. We are not camping because we want to explore Namibia on the cheap, but because the experience we have camping cannot not be got by staying even in a luxury lodge.

We feel bad that camping means we are depriving local people of employment and income, so we like to donate to local schools and communities. In 2020 the conservancy building was well maintained and thriving. This year it looked run down, and was manned by a few poorly dressed individuals, although a uniformed manager did arrive later on.

Everywhere we went seemed depleted from 2020. The animals depleted by, we assumed the drought, and the villages hit by Covid and drought. Covid may have been a problem for us in the UK, but the people here in Namibia were truly suffering, in a way people in Europe could not conceive. They were so thin. We had learnt to recognise those who had work, because they were a ‘normal’ weight. Although Covid had brought deaths, it had also caused large unemployment. Some of the lodges had kept staff on a limited rate, some had just abandoned them.

We went from the conservancy office to the school next door to find Magnus’s son. The school was lively and had a surprisingly young headmistress. We gave another donation. The donation seemed small to us, but she was so delighted she wanted to take our photo. It made us feel a bit bad that such a small amount would cause that reaction but I was becoming concerned about how quickly our cash was going. It was not as if we would find ATM’s, and I hadn’t realised our campsites would be so relatively expensive. We were paying about the same as we would in Europe, not that I begrudged that, I was just surprised.

The school found Magnus’s son, who arrived looking surly, and was much older than I expected. I think he said he was 19 which seemed rather old to still be studying at school. He was hoping to go to university in Windhoek to study engineering. He asked us to take the food to his lodgings, which was with the manager at Sesfontein Fort. This was OK as we were going there anyway, but when he asked us to telephone him at 2pm we did feel he was being a little demanding.

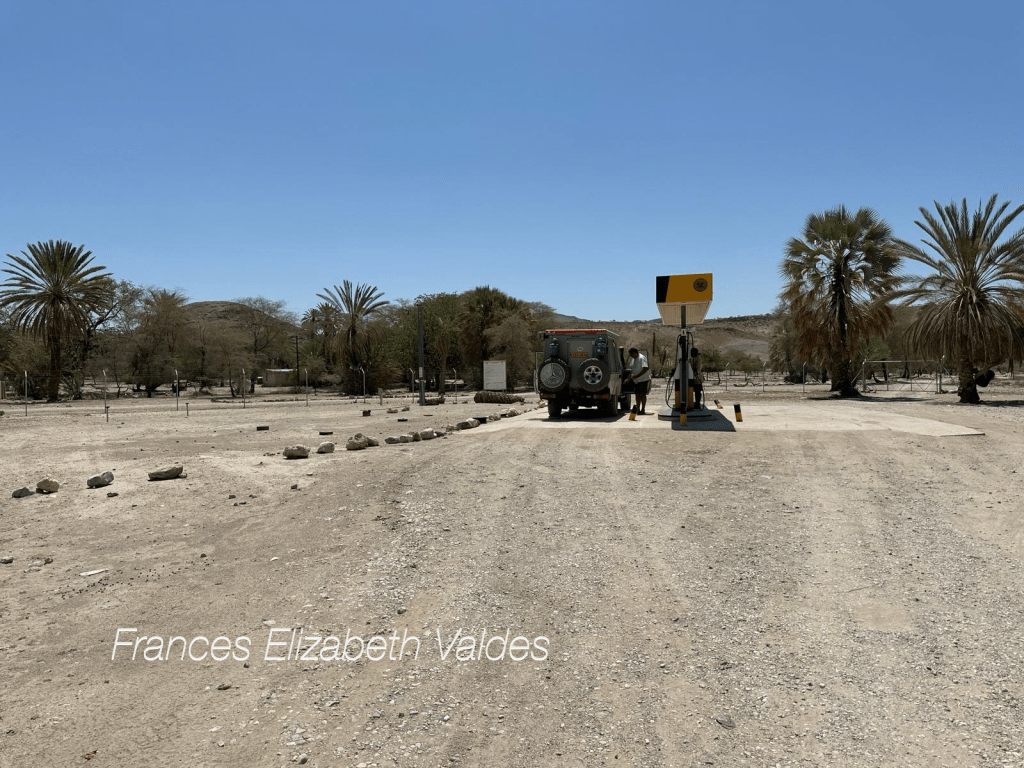

We got fuel and then went to Sesfontein Fort. This was an old German fort which had been turned into a lodge. It had a spring and Magnus had asked us to fill up his drinking water bottles there.

The water at Elephant Song was not good for drinking – too salty I think. We gave the food to the manager and I stayed talking to him, while Nigel filled up the bottles. The manager said the Fort management had divided the staff into four groups during Covid, and each group worked/were paid for one in four weeks.

The manager went on to say that the school was closed during covid, which meant he had to feed his children on his reduced salary (they would have been boarding at the school). He took the children home to his farm in the countryside. When most non-white Namibians talked of a farm, they usually meant a shack and a few goats somewhere rural. He mentioned that he had taught the children to milk goats. I got the impression that they did not see themselves in this kind of rural environment. Eventually, they ran out of food and he had to kill the goats, which of course impacted his future income, as he now had no goat to sell.

We drove on to the main square. In 2020 this was a thriving hub with lots of people milling around – now it was empty There were a few people sitting outside.

One of the two food shops in the square was almost empty of products. I felt so sorry that it had nothing to buy, that I ended up buying some biscuits just to help. The shop assistant had recently started and was unable to calculate the price, and work out change – even though she had a calculator. She was however, immaculately dressed with makeup and a fashionable hairstyle. She was on her phone when we arrived and barely looked up. It is tempting to imagine that young people are the same everywhere in that regard. But the chances are she couldn’t afford a sim card. Most young people used their phone to play games rather than connect. The other difference is that, most western young people aren’t slim, because they can’t afford to be fat!

The second store was reasonably well supplied, but had no vegetables which was what we were particularly craving. The cashier, who also appeared in charge, looked bored. The store had a number of young people lying on top of bags of maize flour, waiting to get a few rand for packing our shopping for us. She had no bread but we got directed to the ‘bakery’

The bakery was also the bar. Bars all over Africa – well certainly in rural areas, are well stocked, but the counters are behind massive iron grills. I’m not sure if it’s to protect the staff from fights, or the bar from pilfering. I guess probably both.

There was a very young girl (well she seemed that way) working there in a disinterested way. We were offered a choice between uncut bread which had just been baked (and was supposedly too hot to cut) or day old bread which was cut. However, after I had complimented her on her hair, which was in a very pretty and elaborate style, we got taken to where she baked the bread to see if she could cut today’s loaf. She could.

The area of baking was littered with abandoned slices of bread, and clearly hadn’t been swept in awhile. The was a young child playing there, who turned out to be the young girl’s son. Later, back at home, I read about the high pregnancy rate at the Sesfontein school. They put it down to the lack of a high wall between the girls and boys dormitories. They had 17 pregnancies last year, amongst the 352 children living in the school hostel.

When we returned to our car there was a big pickup truck (called a bakkie in these parts) full of maize flour labelled drought relief.

We had flown to Namibia, and rented a vehicle for four weeks, but people here were faring so badly the government was giving them maize meal to help with the drought. Life is unfair.

It was strange driving back to Elephant song and the Hoanib. We come to Namibia to enjoy the isolation of deserts and landscapes, but so often it’s the encounters with people which we take home with us. We were at the same time relieved to be back in the desert, but sorry to leave the people we had met.

It was early afternoon as we left the gravel road. Each day the heat had been unbearable at this time. I hate putting on air conditioning in a car, it make me feel I’m in a podule remote from the world I’m driving through. However, we were beginning to recognise we got irritable with each other if we didn’t put the air conditioning on by at least 2pm. So we did.

By the time we got back to Elephant Song and gave Magnus the things we’d bought for him, the strong wind was back. We spent the rest of the afternoon sheltering from the wind and just looking out over the mountains and Okambonde Plains. We never tired of the sight in all the times we were there.